Praise to the Sons of Noun

A four-week trip to the west African country of Niger, where I went to work on a documentary project about the eponym river, saw me travelling some five hundred kilometres along Africa’s third longest river, the Niger River. Drawing its source from Guinea, the Niger River runs through Mali, Niger, along the northern borders of Benin and finally through the length of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country.

My love affair with Niger began several years ago, following the screening of the 1989 documentary “Wodaabe, herdsmen of the sun”, by Werner Herzog. My real encounter with Niger later on, however, was to lead to a more profound communion with the great river, the land and the people.

At the first shaft of the early morning sunlight, Niamey, the country’s capital, quickly swells into a throbbing swarm of pedestrians and a myriad of vehicles, with all and sundry in quest of a good fortune or a few coins. And a good serving of “riz-sauce”, the national dish, is a worthy compensation. As the day wears on, Niamey’s endless stretch of red banco-brick houses and the immense Niger River bed in the horizon paint an enchanting backdrop.

The origin of the name Niger has proved enigmatic among modern researchers, and thus cannot be traced with certainty. The most accepted hypothesis is that the name derives from the Tuareg word: “gber-n-igheren” or “river of all rivers”. In the Timbuktu region the word is shortened to “ngher”.

Since time immemorial, the Niger River has been a meeting point and a place of exchange among various ethnic groups. A genius loci, the river has served as a depository of myths and legends, as well as being the abode of great deities like Ba Faro (mother of humanity) and the all-important Noun. The Niger River is a fountain of living waters and a breath of life. Today, riparian communities count over a hundred million people, from the highlands of Guinea to Port Harcourt in Nigeria.

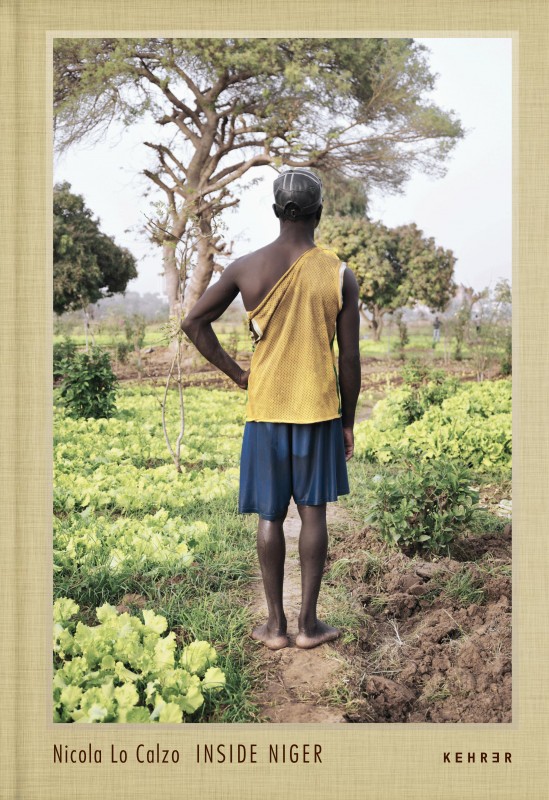

As I traversed the country during those hot and hazy February days, a microcosm of characters and crafts unfolded before me as merchants, priests, butchers, tanners, gardeners, teachers, fishermen, potters, men and women continually renewed their alliance with the murky waters of the river. The encounter was natural, without a middle-man.

Beyond their occupations, individual psychologies and personalities emerged. And people’s trades embodied and shed light on their individual personalities. Along the river, from the western city of Ayorou via Tillaberi, Tera and Niamey to the banks of the lush and evergreen park of « W », I shared in bits and pieces of the daily grind of a country that rests on a fragile equilibrium, sketched by the waters of the Niger river, the desert winds and the influence of an increasing number of anthropogenic activities.

Whilst a harmonious and respectful relationship between man and his environment can be discerned through these portraits, the threat of drought, which threatens to deprive peasants of their already meagre resources, as well as the looming peril of desertification on riparian activities, looms. To save the river is to save the people, both guardians and custodians of Noun.

Nicola Lo Calzo