In Remembrance of Slavery: Tchamba Vodun

In West Africa, slavery represents a past that is difficult to accept, both morally and socially. Memories of slavery have not disappeared, and they have been incorporated into narrative forms that are different from the official versions of history promoted by governments. There are family memories inscribed in the everyday lives of people that were directly or indirectly involved in slavery and the European slave trade.

In the Gulf of Guinea, along the coast from the Volta River in Ghana, through Togo to the westernmost region of Benin, local populations (of Mina and Ewé origin) practice one of the lesser-known religions but which at the same time is among the most representative for the understanding of the history of modern Africa and the memory of slavery in Africa: Tchamba vodun, also called Mami Tchamba.

Tchamba is the name of a spirit considered to be amongst the most powerful and dangerous in the region. It is the spirit of the slaves, men and women who were deported from the north to the southern coast as part of local domestic slavery systems and, more broadly, the Western trade of enslaved Africans. Its worship is the living expression of a historical consciousness of slavery among the local populations.

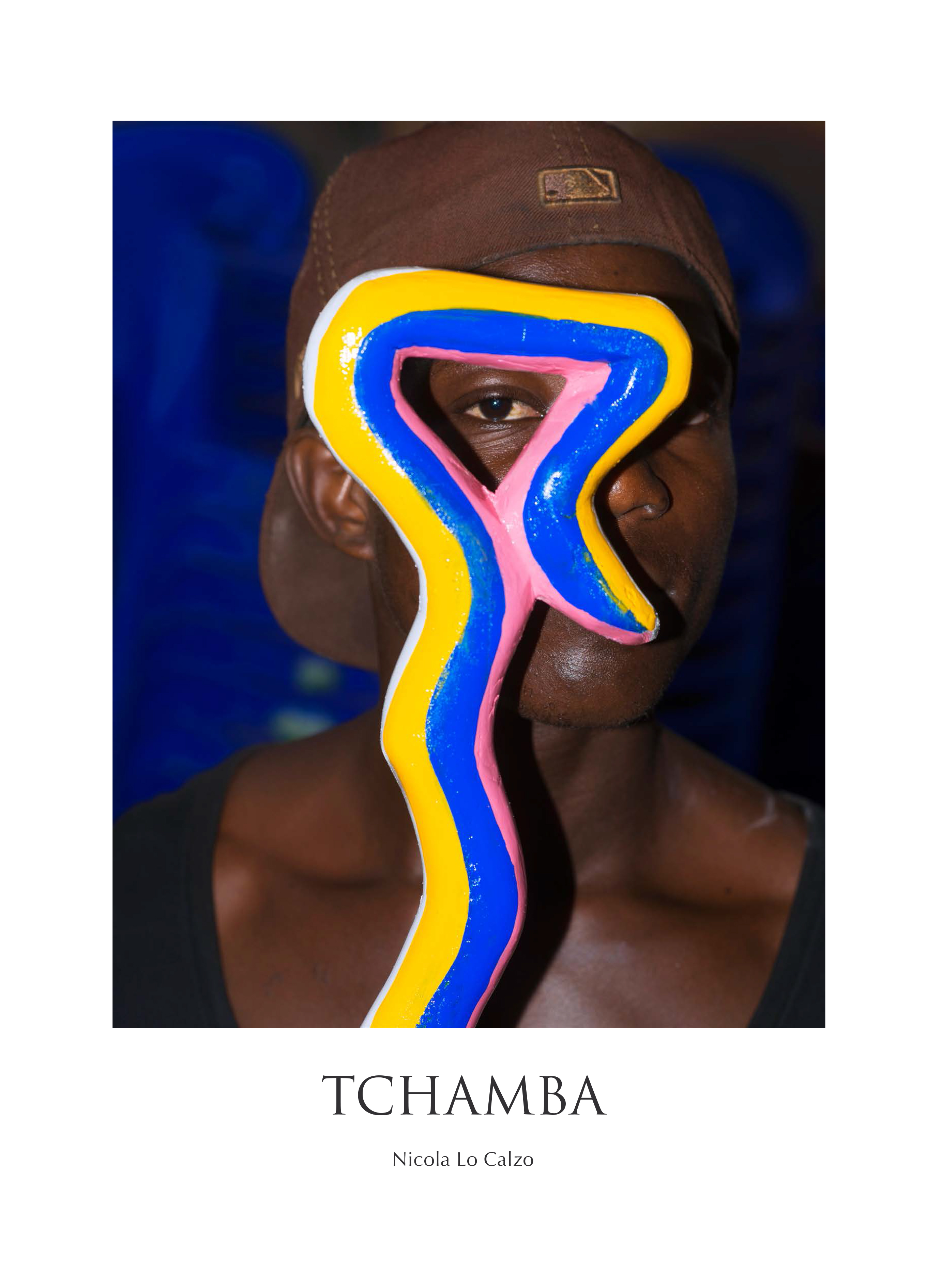

The photographic series presented here is the result of two journeys between 2011 and 2017 in Togo and Benin, and it explores the complexity of this vodun religion, which is a unique pratice that embodies the ambiguities of the memory of slavery and its multiple meanings within local society.

For the local populations, the word Tchamba is polysemic: above all, it refers to a geographical place, the village of Tchamba in the central region of Togo, from where – according to local oral accounts – most of the slaves were deported to the coastal region. It also refers to the ethnic group of the region, which, along with the Kabre, was among the main victims of the raids, wars and trafficking that haunted the territory under pressure from European powers. In addition, Tchamba gives its name to the vodun religion and the spirit that governs it: it is the spirit without peace of a person who died in slavery who was abandoned and deprived of the proper funeral rites. The spirit comes back to the descendants of his or her former master to demand offerings and ceremonies in its honour, the only way to appease its worries and restore order, peace and prosperity within the family.

Historically, Tchamba vodun was shaped in a territory where domestic slavery and the West African slave co-existed during the nineteenth century. Indeed, the transoceanic phenomenon of the West African slave trade fed the local slave trade, which was managed by some wealthy African (and Afro-Brazilian) families in the coastal regions. Following Great Britain proclamation of the abolition of the legal slave trade in 1807, the increase in illegal trade was accompanied by a gradual reconversion of the economy into extensive palm cultivation and the development of a new mode of production: domestic slavery.

The Tchamba worship is, in most cases, associated with women amafleflewo ("bought person") intended for domestic work and work in the fields. Unlike men – the majority of whom were deported to the European embarkation points on the Slave Coast and successively shipped to the Americas (Middle Passage) – most of women stayed in the service of local African masters. They became their mistresses or wives, thus joining their master’s family's clan and giving rise to a new lineage. Other times, there were men who were chosen to be employed in forced labor in the fields. When they died, their bodies were buried outside the village in an area bordering the forest (zogbé) that was associated with the world of the unknown, the irrational and the savage. The spirits of these slaves joined the kingdom of "hot" or "nervous" spirits belonging to people or animals that died in violence (vumeku, literally "death in blood"). That is not by chance that the Tchamba religion is often associated with another important local vodun: Ade, the “hunter” and the deity of the hunting, who is also connected with the world of the hills and forests.

Because of these unstable and painful conditions, Tchamba asks and demands to be respected and honoured by the living with prayers and ceremonies, without which, a family could be led to ruin, to sickness and, at worst, to death. The Tchambassi, the wives of Tchamba, are the followers of this religion, which in the Mina region is linked with the feminine, the female being and is also called Mami Tchamba or Maman Tchamba (like Mami Wata, the deity of water, rivers and seas). They live (partially or all day) in a vodun convent with a Tchamba shrine, under the guidance of a hounon (a vodun priest or a priestess). Their most important symbol is a tri-coloured metal bracelet called a tchambagan. A person wearing this type of bracelet can be recognised as being affiliated with Tchamba and associated with slavery as either a descendant of slaves or slave owners.

These women have a "historical" relationship with their slave ancestor. Often, they are members of the families of the former masters that owned him or her during their life. That said, there is a certain ambiguity in the nature of this vodun. Because the domestic slaves were mostly women, who were then married to their masters, the Tchamba disciples can claim a double origin, being a descendant of both slaves and their masters. As Kokou Atchinou, the Supreme Authority of Vodun in Togo, says: "Not everyone can practice Tchamba. It is not like other vodun. If you have the money, you can set up any other vodun shrine at your home. But if you do not have an ancestor who was involved in this trade [of slaves], you cannot have the Tchamba shrine."

When there is a problem in a family (a business in crisis, a disease, a surprise death) the oracle Afa is consulted and the family learns that the origin of the trouble is a Tchamba spirit and the difficult past inherited by the family. At that moment, still with the oracle, the bokono (the diviner) tells them to create a Tchamba shrine, advises them about the ceremonies needed in order to appease the spirit and reveals to them which honoun can guide the family on this new religious path. This is a long and costly process for the family. Once the Tchamba shrine is built, it is obligatory to respect the spirit, to organise prayers regularly, to make offerings and to hold ceremonies in its honour.

The ceremony – which varies according to place, family and oracle – is the most elaborate and complex aesthetic moment in the life of the followers. Strangers, like myself, must first consult with the Tchamba spirit hosted in the convent to have permission to enter the temple, to speak with the followers, to take part in the ceremony and to take pictures. The flexible nature of vodun, which constantly takes shape in space-time without ever crystallising into a system of dogma and always integrates new elements, making each ceremony singular and unique.

Through a complex ritual, Tchamba vodun highlights the power relationship between former master and his slave. This relationship makes me think of the Hegelian dialectic of the master and the slave, of which the Tchamba religion seems to be create a powerful representation.

This staging is realised through two fundamental moments: sacrifice and trance. With the sacrifice, the practitioners offer Tchamba spirits the animals and the food necessary to obtain their favour. Kokou Atchinou, the Supreme Authority of Vodun in Togo, says: "Now that they have returned, we must respect them, honour them, so that they make life easier. At that time, the slaves ate the leftovers of the master's food. Today, it is the opposite. Now that they have become spirits, they are the first to be fed during sacrifices. We eat after them."

This symbolic reversal of the master-slave relationship also takes place in the case of trance, the psychophysical condition by which the followers are possessed by the spirits of slaves. In a mimetic relationship with the enslaved ancestor, the followers – descendants of the former masters – eat, talk, dress and behave according to the presumed customs of slaves owned by their families. The “savage” and “irrational” north is the imaginary or real place from which the slaves are supposed to originate. The follower, possessed by the spirit of Tchamba, yields to its will, lets himself or herself be guided by the spirit and submits to its orders. He or she becomes the "slave" and, in so doing, restores lost balance and harmony within the family.

Followers become aware of themselves in the dynamic relationship of the present and the past. Thus, this vodun has a double-edged social function: on the one hand, reconciling the living with their slave owner or slave past, honouring the spirit of the slave and pay it respect. On the other hand, it has a practical function: to keep bad luck away, to ensure the prosperity of relatives and to affirm the prestige incarnated by their own slaving history. Indeed, the family history does not induce any real sense of guilt among the descendants. In most cases, on the contrary, the slave past is a proof of the former family wealth. Far from a Manichaean view of the world, peculiar to monotheistic religions, Tchamba vodun shows a certain opacity, ambiguity and polysemy, explains Kokou Atchinou, the supreme authority of vodun in Togo: "It was the Europeans who came to us and asked for robust people to go and work in their fields. Little by little, we started this trade to satisfy this demand [...] Not everyone had the money to buy. For us, we are proud to be the son of someone who participated in this trade. But we are also obliged to accept these spirits and pay them their due respect."

In gaining this awareness of family history, the Tchamba followers reactivate the memory of slavery, share it and transmit it to future generations. They recognise a place for the spirit of the person who died enslaved in the family pantheon and in the community. Tchamba leaves the restless world of the forest and, at least during the time of the ceremony, finds peace at the family shrine, the meeting place between the visible and the invisible world, between past and present, between ancestors and descendants, between former masters and former slaves.

Nicola Lo Calzo